Having toyed with the ideas from Getting Things Done and not really getting much out of it, I thought I’d revisit David Allen’s ideas with a little more rigour. I’d causally read some articles, skimmed the book, downloaded the app but all I ended up with was a bunch of lists on my phone. I’d look at them every now and then but I didn’t exactly achieve the zen like effectiveness Allen talks about. This time, I thought, I’d have a proper go; practice the principles across all aspects of my life and reflect my experience in a few short articles. Here I go.

In this first post, I’ll talk a little about Allen’s ideas, summarising the first section of the book. In the second post, I reflect a little on it’s application and the changes I made to my personal approach to getting things done.

Open Loops and Front-end Decisions

Allen begins by defining two key objectives; to capture all the things you need to get done in a trusted system and being disciplined to make front-end decisions about these inputs.

The things that need to get done represent “open loops”. Anything that demands your attention, if only for a moment. The idea here is that by capturing them, you’re freed up from worrying about them. Capturing them in a system that you absolutely trust is key. You must have faith that the system not only records the inputs but helps you process them in a way that works for you. You have to be confident that you’re not just brushing them under the carpet, that you’ll got back to the system and that it’ll work.

I decided the only way to know if I could trust Allen’s system was to try it.

From Inbox to Options

Allen suggests that if something is “on your mind”, you want it to be different than it currently is. He defines this “stuff” as anything that is on your mind that you haven’t yet determined the intended change or next steps to achieving it. So perhaps the first insight is to move from a simple list of “stuff” or partial reminders into a an inventory of actionable tasks that move us towards our objectives.

A summary of actions and front-end decisions that need to be made for all “open loops” is

- Clarify the intended outcome. Quantify the results. When is it done?

- Decide the very next physical action that will take you towards that goal

- Put reminders in place of the two previous steps

I visualise this process as moving from a general dumping ground; the “inbox” to an “options” list. The list of concrete things I could do. To move from one to the other, I go through the steps above. To solidify the movement, I move tasks from one physical list to another, rewording and strengthening the description. At this point, I’m not concerned with dates or follow up tasks, just in getting things off of my mind and onto paper.

The Workflow

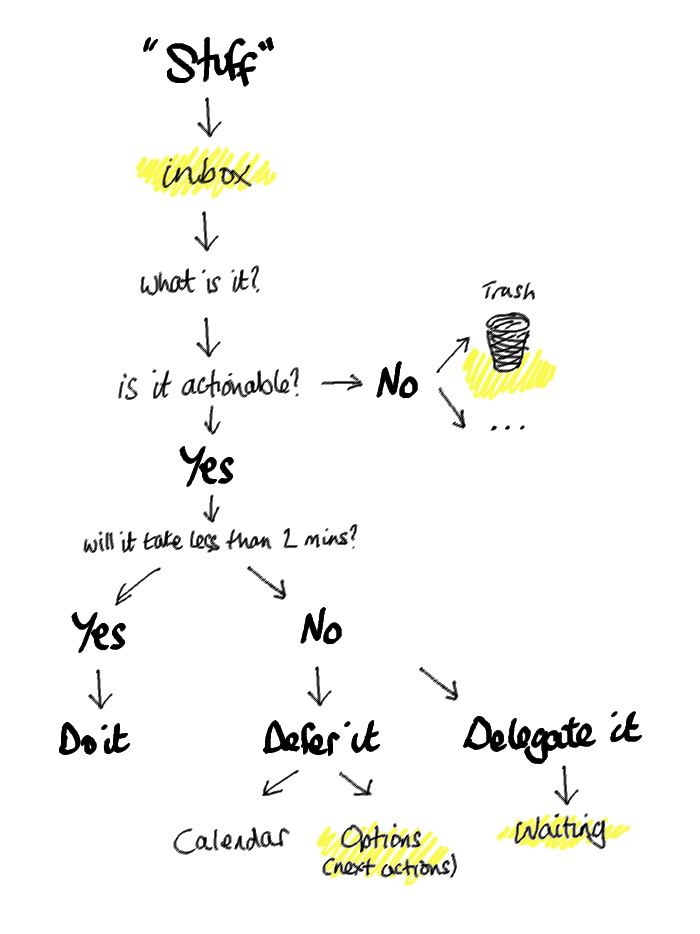

So far, I’ve focused on what I interpret as the core principle; to get things off of your mind and into a trusted system. It’s probably a good time to introduce a few other of Allen’s ideas; namely the different list types and a basic workflow. In a slightly simplified form, Allen’s workflow looks like the diagram opposite.

It describes the journey from “stuff” to either some concrete action (do it) or one of the other lists Allen talks about (the yellow leaf nodes). It describes how firstly, any “open loops” get captured in an “inbox”. Raw data capture, nothing fancy. The next step (what is it?) is to apply the first front-end decision and quantify the objective. The next step (is it actionable?) is about identifying the next definite step you can take; firming up the next action.

At this point, if its not actionable, it’s either binned (trash) or moved to some other list (…). If it is actionable and quick, just do it. Otherwise, the next step is moved to another list. Either a list of “options” or after delegating it, a list to track external dependencies (waiting). The calendar captures tasks that have a definitive date associated with them.

So, we’ve clarified our intended outcome, decided the next physical action to take and recorded that action in an appropriate bucket. The next thing is to put reminders in place. For this, Allen doesn’t prescribe any particular system. You may feel Outlook fits the bill or find a tool that “supports” Getting Things Done on your phone.

Summary

I’ve missed a lot out here. I’ve skipped over projects, contexts and a bunch of other stuff. I found it easier to absorb the basic principles like this though and in the next post, we’ll have a look at some examples where I’ve tried to apply just these basics to my own list of “stuff”.